CHEAP TRAVEL EUROPE

Raphael's tapestries

During occasional ceremonies of particular importance, the side walls are covered with a series of tapestries, the originals of which were designed for the chapel by Raphael and depict events from the Life of St. Peter and the Life of St. Paul as described in the Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles: the full-size preparatory cartoons for seven of the ten tapestries are known as the Raphael Cartoons and are in London.[11] Raphael's tapestries were looted during in the Sack of Rome in 1527 and were either burnt for their precious metal content or were scattered around Europe. In the late 20th century, a set was reassembled (several further sets had been made) and displayed again in the Sistine Chapel in 1983.

[edit] Decoration

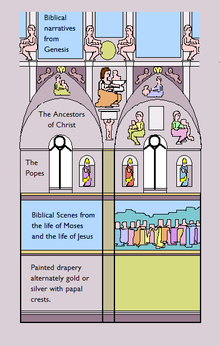

The walls are divided into three main tiers. The lower is decorated with frescoed wall hangings in silver and gold. The central tier of the walls has two cycles of paintings, which complement each other, The Life of Moses and The Life of Christ. They were commissioned in 1480 by Pope Sixtus IV and executed by Ghirlandaio, Botticelli, Perugino, and Cosimo Roselli and their workshops. The upper tier is divided into two zones. At the lower level of the windows is a Gallery of Popes painted at the same time as the Lives. Around the arched tops of the windows are areas known as the lunettes which contain the Ancestors of Christ, painted by Michelangelo as part of the scheme for the ceiling.

The ceiling, commissioned by Pope Julius II and painted by Michelangelo between 1508 to 1512, has a series of nine paintings showing God's Creation of the World, God's Relationship with Mankind, and Mankind's Fall from God's Grace. On the large pendentives that support the vault are painted twelve Biblical and Classical men and women who prophesied that God would send Jesus Christ for the salvation of mankind.

In 1515, Raphael was commissioned by Pope Leo X to design a series of ten tapestries to hang around the lower tier of the walls.[12] Raphael was at the time twenty-five and an established artist in Florence, with a number of wealthy patrons, yet he was ambitious, and keen to make an entry into the patronage of the papacy.[13] Raphael was attracted by the ambition and energy of Rome.

Raphael saw the commission as an opportunity to be compared with Michelangelo, while Leo saw hangings as his answer to the ceiling of Julius.[14] The subjects he chose were based on the text of the Acts of the Apostles. Work began in mid-1515. Due to their large size, manufacture of the hangings was carried out in Brussels, and took four years under the hands of the weavers in the shop of Pieter van Aelst.[15]

Although Michelangelo's complex design for the ceiling was not quite what his patron, Pope Julius II, had in mind when he commissioned Michelangelo to paint the Twelve Apostles, the scheme displayed a consistent iconographical pattern. However, this was disrupted by a further commission to Michelangelo to decorate the wall above the altar with The Last Judgement, 1537-1541. The painting of this scene necessitated the obliteration of two episodes from the Lives, several of the Popes and two sets of Ancestors. Two of the windows were blocked and two of Raphael's tapestries became redundant.

[edit] Frescoes

[edit] Christ Giving the Keys to St. Peter

Among Perugino's frescoes in the Chapel, the Christ Giving the Keys to St. Peter is stylistically the most instructive. This scene is a reference to Matthew 16[16] in which the "keys of the kingdom of heaven" are given to St.Peter.[17] These keys represent the power to forgive and to share the word of God thereby giving them the power to allow others into heaven. The main figures are organized in a frieze in two tightly compressed rows close to the surface of the picture and well below the horizon.[18] The principal group, showing Christ handing the silver and gold keys to the kneeling St. Peter, is surrounded by the other Apostles, including Judas (fifth figure to the left of Christ), all with halos, together with portraits of contemporaries, including one said to be a self-portrait (fifth from the right edge). The flat, open square is divided by coloured stones into large foreshortened rectangles, although they are not used in defining the spatial organization. Nor is the relationship between the figures and the felicitous invention of the porticoed Temple of Solomon that dominates the picture effectively resolved. The triumphal arches at the extremities appear as superfluous antiquarian references, suitable for a Roman audience. Scattered in the middle distance are two secondary scenes from the life of Christ, including the Tribute Money on the left and the Stoning of Christ on the right.

The style of the figures is inspired by Andrea del Verrocchio.[19] The active drapery, with its massive complexity, and the figures, particularly several apostles, including St. John the Evangelist, with beautiful features, long flowing hair, elegant demeanour, and refinement recall St Thomas from Verrocchio's bronze group in Orsanmichele. The poses of the actors fall into a small number of basic attitudes that are consistently repeated, usually in reverse from one side to the other, signifying the use of the same cartoon. They are graceful and elegant figures who tend to stand firmly on the earth. Their heads are smallish in proportion to the rest of their bodies, and their features are delicately distilled with considerable attention to minor detail.

The octagonal temple of Jerusalem[20] and its porches that dominates the central axis must have had behind it a project created by an architect, but Perugino's treatment is like the rendering of a wooden model, painted with exactitude. The building with its arches serves as a backdrop in front of which the action unfolds. Perugino has made a significant contribution in rendering the landscape. The sense of an infinite world that stretches across the horizon is stronger than in almost any other work of his contemporaries, and the feathery trees against the cloud-filled sky with the bluish-gray hills in the distance represent a solution that later painters would find instructive, especially Raphael.

The fresco was believed to be a good omen in papal conclaves: superstition held that the cardinal who (as selected by lot) was housed in the cell beneath the fresco was likely to be elected. Contemporary records indicate at least three popes were housed beneath the fresco during the conclaves that elected them: Pope Clement VII, Pope Julius II, and Pope Paul III.